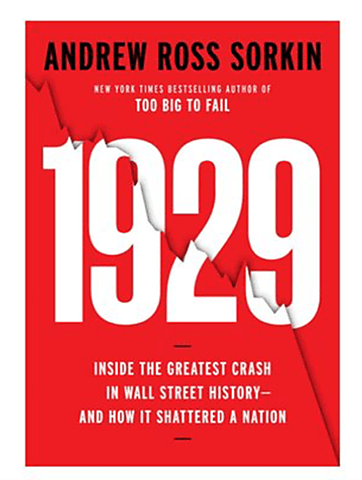

Andrew Ross Sorkin’s blockbuster, 1929: Inside the Greatest Crash in Wall Street History—and How It Shattered a Nation, seeks to explain the stock market crash and the Great Depression. His approach is to paint a narrative by considering “the motivations and disparate stories of the central actors” (p. x). These include the heads of major financial firms, businesses, the New York Stock Exchange, and the Federal Reserve, as well as politicians, speculators, economists, and journalists.

There is no table of contents for the 567-page book, only an opening list of “The Cast of Characters and the Companies They Kept.” Each chapter heading is a specific date in the narrative, beginning with February 1, 1929, and ending with June 21, 1938. There are 443 endnotes, an extensive bibliography, and an index. The book took more than eight years to produce. It was published in 2025 by Viking.

Although Sorkin does an excellent job of describing the main characters in the narrative, he fails to fully understand and convey the fundamental causes of the crash and depression. He overplays the role of speculation leading up to the market crash in October 1929; largely ignores the monetary causes of the deep depression, in which the stock of money fell by one-third between 1929 and 1933; and never addresses the flaws in the “Real Bills Doctrine” that misguided monetary policy. There is no mention in the book of: (1) the path-breaking work of Clark Warburton, who, in the mid-1940s and early 1950s, provided a detailed analysis of the monetary causes of business fluctuations [see Warburton 1966: Depression, Inflation, and Monetary Policy: Selected Papers, 1945–1953]; (2) Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz’s monumental Monetary History of the United States [1963]; or (3) Thomas Humphrey and Richard Timberlake’s Gold, The Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed: Sources of Monetary Disorder, 1922–1938, which appeared in 2019.

Phil Gramm, former chairman of the Senate Banking Committee, calls the Humphrey-Timberlake (H‑T) book “the most important book written on the Great Depression” since Friedman and Schwartz’s Monetary History. According to Gramm, “The book points to an obscure and largely forgotten theory, the Real Bills Doctrine, as the culprit for the failure of the Federal Reserve … to respond to the collapse of the money supply, which turned a financial panic into a Great depression” (from the front matter in H‑T). It is a shame that Sorkin was unaware of this 201-page book.

For Sorkin, “the story of 1929” is about “human nature” and “irrational exuberance.” And “the antidote” is “humility to know that no system is foolproof” and “no market fully rational” (p. 444). Of course, no human or system is perfect. What needs to be done is to understand the forces that shape institutions, why they fail, and how to improve them. This is especially true for monetary institutions. Sorkin’s “story” could have benefited from the work of Warburton, Friedman and Schwartz, and Humphrey and Timberlake—all of whom recognized the importance of sound money in the operation of a market price system. A summary of their ideas follows.

Warburton on the Key Role of Monetary Stability

From his extensive statistical work and knowledge of monetary disequilibrium theory, Warburton came to the conclusion, after 1945, that “the chief originating factor in business recession” is “an erratic money supply” (Warburton 1966: p. 9). He found that the key factor leading to variation in the quantity of money was “variation in bank reserves” (p. 10).

As early as 1946, Warburton argued that the Federal Reserve’s failure to prevent the Great Depression was “a result, in part, of the inadequacy of the monetary theory underlying the [Federal Reserve] Act and, in part, of the failure to carry out in practice the theory which was embodied in the Act” (Warburton 1966: p. 301). According to Warburton, “The monetary deficiency preceding each business depression since establishment of the Federal Reserve System—1921, 1924, 1927, 1930–33, and 1937–38—has been produced by Federal Reserve action impinging on the quantity of bank reserves” (p. 315).

In particular, if the Fed had taken into account the importance of monetary deficiency, relative to the demand for money, the Great Depression could have been avoided. By focusing on preventing speculation, rather than thinking in terms of a suitable quantity of money to provide for normal production and price stability, the Fed was led to restrict money growth rather than expand it to maintain total spending and income on a level growth path (see Dorn 2022).

From his careful investigation of the 1920s and 1930s, Warburton (p. 114) concluded that, during the years 1923–1928, money growth was largely in line with real economic growth, and the price level was relatively stable—“indicating that the rate of increase in the volume of money was not excessive.” However, in the late 1920s, the Federal Reserve restricted the growth of bank reserves and allowed monetary growth to fall below its long-run trend. Outright contraction in the money supply occurred in the early 1930s, causing deflation and depression (p. 98).

In examining the Annual Reports of the Federal Reserve Board, Warburton found that, for the 1929 report, the Fed acknowledged its intensive use of “direct pressure” to stem speculation, but the board did not feel it was necessary “to estimate the general expediency or the major public consequences of its intervention” in credit markets (p. 308). “The major public consequence of Federal Reserve action in 1928 and 1929,” noted Warburton, “was a stoppage of normal growth of the nation’s money and initiation of the monetary contraction, which eventuated in the Great Depression and the banking crisis of 1933.” In effect, the Fed repudiated its “responsibility for monetary policy” and discarded its “previous emphasis on the quantitative aspects of bank credit.” In this reversal, the Board elevated qualitative considerations into the position of sole criterion for central bank action.” (p. 308).

In examining the Fed’s 1931 report, Warburton stated that the Fed showed no awareness “that the sharp decrease of member bank reserve balances in the last quarter was due to inadequate provision by the Federal Reserve banks of reserves to meet the public demand for conversion of one kind of money (bank deposits) into other kinds (circulating notes and gold).” Moreover, the Fed did not recognize that this failure “was the major cause of the contraction of bank loans and investments” (p. 304, n.10).

From a review of the Fed’s 1932 report, Warburton concluded that the central bank failed to recognize and utilize the Board’s emergency power “to suspend reserve requirements for member banks and for Federal Reserve banks—powers that were fully ample to handle the problem of monetary convertibility without contraction of bank loans and investments” (ibid.).

Finally, Warburton argued that the 1933 report showed “no awareness … that loss of confidence by bank customers in the solvency of their banks would not have produced monetary contraction were it not accompanied by the failure of the Federal Reserve System to provide monetary convertibility.” Nor was the Fed aware “that the great depth of the depression, with its drop in prices of all classes of property, was primarily due to the monetary contraction of the preceding four years.” In turn, the Fed was not cognizant “that the crisis was therefore a monetary crisis with the bank insolvencies largely a consequence of the monetary crisis” (pp. 304–5, n.10).

In sum, Warburton was a pioneer in developing a monetary theory of the Great Depression (see Bordo and Schwartz) and in calling for a rules-based monetary policy. Sorkin could have enhanced his story of the crash and depression had he incorporated Warburton’s early insights.

Friedman and Schwartz on the Great Contraction

Friedman and Schwartz, in their classic Monetary History of the United States, came to many of the same conclusions reached earlier by Warburton. They blamed the Fed for the “Great Contraction,” in which the money supply fell by one-third during the years 1929–1933, making what would have been a temporary recession into the Great Depression with massive bank failures, deflation, sharply falling output, and a quarter of the work force idle. Like Warburton, they argued that the Fed had the power to return money growth and nominal income to normality, but remained passive. As they wrote: “At all times throughout the 1929–33 contraction, alternative policies were available to the System by which it could have kept the stock of money from falling, and indeed could have increased it at almost any desired rate” (Friedman and Schwartz [1963] 1971: p. 693).

The policies that were needed to restore confidence and get the economy moving again, according to Friedman and Schwartz, “did not involve radical innovations.” Rather, “They involved measures that were actually proposed and very likely would have been adopted under a slightly different bureaucratic structure or distribution of power, or even if the men in power had somewhat different personalities” (ibid.). Here they had in mind (1) the shift of power that occurred in the Federal Reserve System after the death of Benjamin Strong, the head of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, in 1928, and (2) the decrease in the New York Fed’s influence—in favor of an expansionary monetary policy following the October 1929 stock market crash—when open market operations were decided by a committee representing all 12 Reserve Bank governors, in place of the previous five-member committee in which the New York Reserve Bank dominated. Those changes, argued Friedman and Schwartz (p. 692), “stacked the cards heavily in favor of a policy of inaction and drift.”

Given the prominence of Friedman and Schwartz’s book, it is puzzling why Sorkin failed to reference it, for it would have helped clarify the causes and consequences of the 1929 crash and Great Depression.

Humphrey and Timberlake on the Real Bills Doctrine

Anyone who wants to understand the forces that led to the monetary disorder in the early 1930s should read Humphrey and Timberlake’s book, which places the Real Bills Doctrine (RBD) at the heart of the Great Contraction/Depression. As eminent monetary historian George Tavlas notes in his review of Gold, the Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed,

The story that Humphrey and Timberlake narrate about the role played by the real bills doctrine in the Great Depression is compelling. It provides a unified interpretation of the two stages of the Depression—namely, the initiation stage, during which the money stock was allowed to decline, and the deepening phase, produced by the banking crises of the early 1930s: Tavlas 2021:174].

He goes on to say, “The authors’ elevation of the real bills doctrine to the role of big bad actor in the Great Depression is original and alluring, thus providing a first-class contribution from the two distinguished performers on the monetary-historical stage” (p. 176).

Likewise, Nobel Prize recipient Milton Friedman has stated that Humphrey and Timberlake’s “emphasis of the Real Bills Doctrine complements in an important way Anna [Schwartz] and my analysis of why Fed policy was so ‘inept’.” The difference is: “We stressed and discussed at great length the shift of power in the System. We did not emphasize, as in hindsight … we should have, the widespread belief in the Real Bills Doctrine on the part of those to whom the power shifted.” (This statement appeared in the front matter of the H‑T book.)

Humphrey and Timberlake (p. 5) boil down the RBD to the basic idea that “the ‘right’ quantity of money would be created if bank credit (in the form of loans to businesses) was tied to output (in the form of goods in the process of production).” Sound banking required that “banks lend against ‘real bills’—commercial paper representing claims to the goods being produced—so that the money stock would vary according to the needs of trade” (ibid.).

The RBD, however, was flawed as a principle to achieve monetary stability. As Humphrey and Timberlake note:

It failed to distinguish nominal from real output. It linked one nominal variable, the money stock, with another nominal variable, the dollar volume of commercial paper. This characteristic meant that the Real Bills Doctrine could not, by itself, establish any effective limits on either money or prices. Once disturbed by disequilibrating shocks, both the quantity of money and money prices could rise or fall unchecked [ibid.].

One key shock to the financial system was “a moralistic fervor against speculation.” In particular, “when the doctrine opposed loans made for ‘speculative’ as distinct from ‘productive’ purposes in 1929–1930, as if they were mutually exclusive, it set in motion a disaster that lasted 10 years” (Humphrey and Timberlake, p. 169).

The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 gave the Fed the authority to lower or remove reserve requirements during an emergency. Thus, Humphrey and Timberlake argue that if the Federal Reserve Board had used its statutory power “any time after 1929, the Fed banks could have stopped the contraction in its tracks, even if doing so exhausted their gold reserves entirely” (p. 170).

Unfortunately, “supporters of the Real Bills Doctrine, who gained control of the Federal Reserve [System] in 1929, treated any bank lending for stock market ‘gambling’ as a vice on a par with the stable price level policy of Benjamin Strong and the New York Fed, which they had repeatedly condemned.” (p. 171). In turn, the Fed initiated a “direct pressure” campaign against “speculation” aimed at controlling “commercial bank lending”—unleashing “an avalanche of bank failures much beyond anything preceding it in the history of banking” (ibid.).

There is no entry for the Real Bills Doctrine in Sorkin’s index or any substantive analysis of the RBD and its fatal flaws. Leaving that discussion out of the book is a serious shortcoming.

The Relevance of Monetary History and Theory

Sorkin’s book is a New York Times bestseller. It makes an important contribution to the literature on the 1929 crash and Great Depression. But it omits important parts of the narrative regarding the causes of the prolonged depression—namely, monetary disorder due to the flawed Real Bills Doctrine.

Why did the Fed passively allow the money supply to decline by more than 30 percent during 1929–1933? That question was answered by Warburton, Friedman, Humphrey, and Timberlake. They carefully examined the facts, developed theories, and tested them against the facts. Their “stories” are worth reading along with Sorkin’s.